The Album Art of Phil Hartmann

You might remember him from such roles as Troy McClure or Lionel Hutz, but in the years before legendary comic Phil Hartman shaved the second ‘n’ from his name, he was designing album art for some West Coast rock bands.

The Phil Hartman story could — and perhaps should — be told in two parts.

In the first story, a charismatic comic goes from the stand-up circuit to Saturday Night Live, becoming an invaluable cast member on America’s most hallowed skit show and graduating to legendary roles on The Simpsons. In the second, an actor on the brink of genuine stardom is murdered, the victim of a terrifying act of domestic violence.

These stories are best kept distinct in order to fully appreciate Hartman, who – like many tragic artists before him – runs the risk of becoming all but synonymous with his sensational death. His life was so much more than his tragic and infamous killing, enshrined not only in his art, but his charismatic personality often celebrated by his many co-stars and collaborators. We’ll never hear him as Zapp Brannigan or see him in the Troy McClure film he was planning, but thankfully, we’ll always have “A Fish Called Selma,” and we’ll never have to go without his pitch-perfect Reagan.

There is, however, a third thread to Hartman’s story, a chapter of public life that’s far less recognized than his indelible screen presence. It picks up long before his charismatic rise to the peak of comedy, when Hartman was more class clown than class act, a Canadian kid moving about the United States. Still going by Hartmann, his birth name, Phil graduated from Westchester High in Los Angeles, taking up art at Santa Monica City College. He soon dropped out to become a roadie for local rock band Rockin’ Foo and, when the group needed art for their debut, his past as a visual art student made him a natural candidate for the job. The four-piece must’ve liked his work, as Hartmann illustrated — and signed — the art to both their first and second records.

In 1972, three years on from dropping out, Hartmann started studying graphic design at California State University. This time around he graduated, but not before taking on some projects from his music scene connections. In ‘72 alone, Phil cut covers for power pop four-piece Bones, boasting an approachable group photo; The Pure Food and Drug Act, whose sole record bears an FDA-inspired stamp; and Pure Food and Drug Act member Harvey Mandel, for whom Hartmann depicted the scale-laden psychedelia of The Snake.

On graduating, Phil opened his own graphic design studio and started taking on commissions. His first big client came to him through his brother, former Geffen-Roberts staffer John Hartmann, who’d recently left that fledgling managerial company and started his own business with Harlan Goodman. Hartmann & Goodman had managed to make away with a couple of Geffen’s clients, including British-American rock trio America — you know what they say, a Goodman is a Hartmann to find — but it was their totally new relationship with country rock band Poco that saw Phil strike up a rapport.

In hindsight, it’s possible to see Poco as something of an odds-and-ends band. That’s not how it was at the time, but the group — founded by Buffalo Springfield alumni Richie Furay and Jim Messina — might be best remembered as a repository for the immense talent within. Bassist Randy Meisner left during their first record, taking the band’s country rock approach to new heights by co-founding The Eagles. His successor in Poco, Timothy B. Schmidt, would later succeed him in The Eagles after tensions led to a vicious backstage brawl. Poco carved out a string of classic rock hits, but their legacy is often positioned between what had been and what would eventually come to pass.

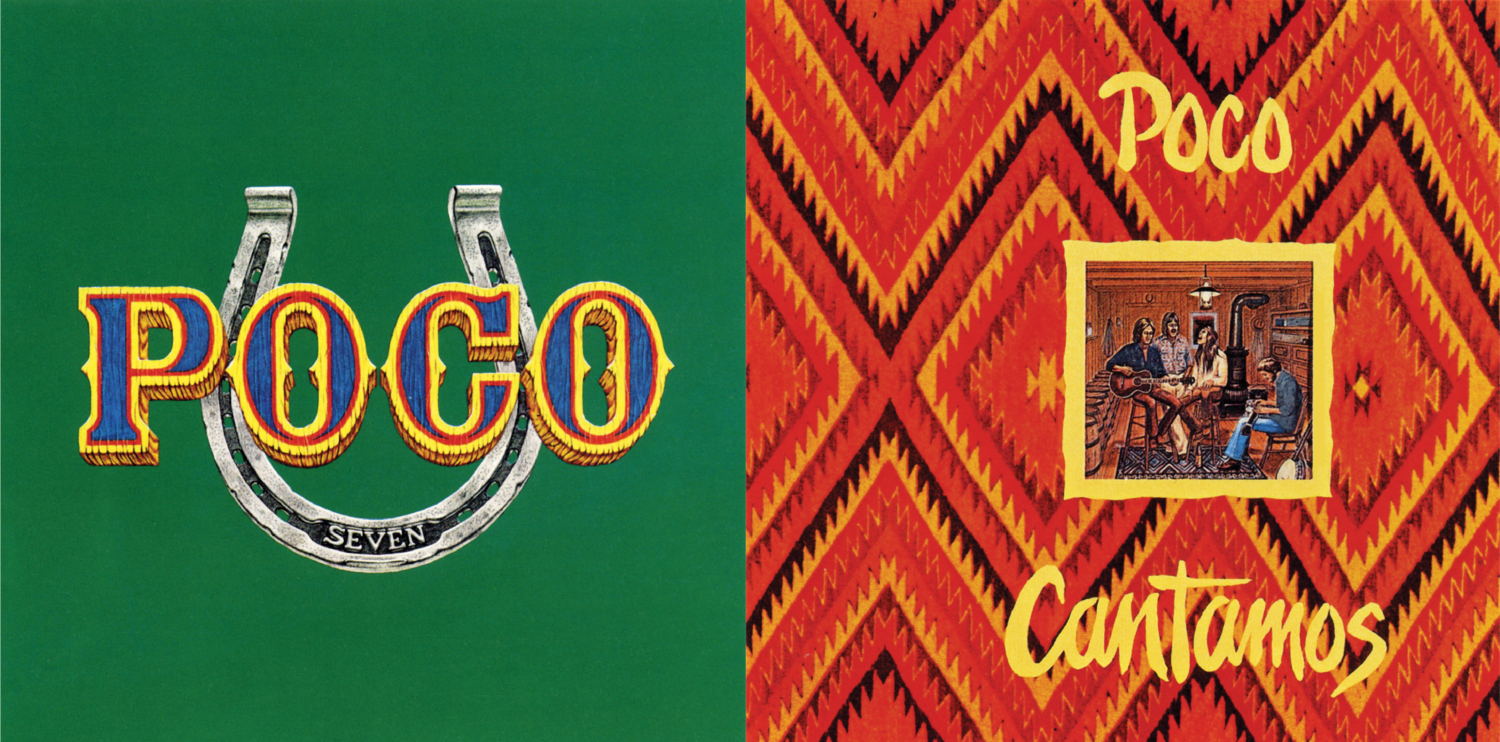

It makes sense that Hartmann & Goodman would have had a connection to Poco, seeing as Geffen-Roberts had managed acts such as Buffalo Springfield’s Stephen Stills and Randy Meisner’s The Eagles in the early 1970s. The first record on which Hartmann & Goodman managed the group, 1974’s Seven, was also the first to boast Phil’s artwork, a minimalist image of an upright horseshoe on a solid green backdrop. If there’s nothing radical about the piece, it does speak to a few simple tenets of the group, imparting luck on their first post-Richie Furay record, tethering them to a classic symbol of country living, and tapping into the folklore of the untamed frontier.

Phil’s second commission came just seven months later, when the quartet dropped Cantamos, a return to their lighter country-rock roots. Phil’s familiar Navajo-inspired textile pattern fits the sound, his folksy ochre palette tethering the Californian record to the distant folklore of the American Southwest. A quaint illustration sits inset, showing the four members jamming away inside a log cabin, flanked by a wood-burning stove. It’s cozy, it’s intimate, it’s unadorned: their electric riffs on hold, the art seems to centre the return of the classic, easygoing Poco.

Hartmann’s graphic design breakout – if it could be called that – came in 1975, the same year that he joined the then-new Groundlings sketch troupe. Phil designed two albums that year: Poco’s Head Over Heels, a poppier tack that nonetheless flopped, and America’s History, a bestselling document of that West Coast trio’s first five years. That’s more on Dewey Bunnell, Gerry Beckley and Dan Peek’s hitmaking prowess than anything else, but Hartmann’s visuals make for a tender front to that premature celebration.

An illustration suspended on a cream canvas, the drawing shows all three members surrounded by glimpses of their own past. Dan Peek, whose cowboy chic is based on a Hat Trick poster, beams from beyond Westminster, an allusion to the group’s beginnings as kids of UK-based USAF personnel. Gerry Beckley, centered, wears a shirt of leaves, a backdrop upon which Hartman sketches the Holiday cover. Dewey Bunnell’s appearance is also taken from a photograph originally released with Hat Trick, with the backdrop of the Golden Gate Bridge a reference to their recent Hearts cover.

That job spawned another rapport and, over the next two years, Hartmann designed Poco’s Rose of Cimarron with Monterey Pop Festival art director Tom Wilkes, and the red-plated Indian Summer all by himself. He continued his streak with America by designing Hideaway, centering band shots by Henry Diltz; Harbor, framing Diltz’s tropical shots in a sunnier palette; and Live, casually laying Diltz’ photograph atop well-worn handwritten notation.

The one and only record by L.A. quintet Silver, featuring the brother of Eagles member Bernie Leadon, was overseen by Hartmann & Goodman. It’s no surprise that Phil was responsible for the fairly simple design, framing pictures taken by prolific music photographer Guy Webster. If these records had seen Hartmann in more unadventurous straits — bulky, patterned and often revolving about the photos of others — his biggest personal achievement came in 1978, when Poco released their eleventh record, Legend.

“I did over 40 album covers, including the white Poco album,” said Hartman in a 1996 interview. “That's the only piece I have up in my office.” More than just a passion project or a point of pride, Legend was both a personal achievement for Phil and a commercial peak for the radically restructured group. Arriving after years of commercial failure, Legend was recorded by Poco members Paul Cotton and Rusty Young, whose decision to start their own outfit was trumped by the label’s need for brand recognition. A radio-friendly pivot surely helped the record sell, but Hartmann’s cover can’t have hurt those figures, his minimalist rendering of a galloping horse befitting the lofty title.

It’s little more than a handful of lines, arranged to both cut a figure and imply a shape unseen. The red eye sits as a solitary splash of colour, drawing the audience’s own to the deceptive simplicity of that eight-line head. It’s not hard to see why the cover ended up mounted on Phil’s office wall – not only is it entirely his own vision and handiwork, but it’s easily a standout in his oft-simple portfolio. It might’ve been the peak, or maybe it was just the best so far: either way, that very year, Phil made his acting debut in Brian Trenchard-Smith’s Ozploitation film, Stunt Rock.

In 1979, Phil’s work with the Groundlings saw him become a leader in the troupe. He helped fellow Groundling Paul Reubens develop The Pee-wee Herman Show, a stage show that found its way to HBO in 1981. All the while, Hartmann took on a few more graphic design commissions, designing art for Michael Murphey’s 1979 record, Peaks Valleys Honky-Tonks & Alleys, which stressed folksy photography; America’s Silent Letter, which saw Phil working with photographer Gary Heery; and The Firesign Theatre’s Fighting Clowns, which fused his worlds of troupe comedy and graphic design.

His final credits include a cover for America satellite Avalon, an AOR trio whose only record bore some graphic similarities to America’s Harbor, as well as two of Poco’s final records, 1982’s Ghost Town and 1984’s Inamorata. These final assignments were the product of faith alone – Hartmann & Goodman hadn’t managed Poco since Legend, and their late return to the younger Hartmann’s vision falls as a vote of confidence. Phil was confident too, but about something else altogether: in 1985, he co-wrote and appeared in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, a role that helped him secure his place at Saturday Night Live. Phil’s graphic design days were over: he dropped the second ‘n’ from his surname, and the newly-christened Phil Hartman stepped to the national stage.

Hartmann, left, with Poco.

On October 11 1986, Phil Hartman made his debut on the 12th season of SNL. It was just two days later that America submitted their revised sales numbers to the RIAA, earning a quadruple platinum plaque for History. That’s more than four million copies in a little over a decade. The band haven’t run the numbers again in the thirty-six years since, but one thing’s for sure: even before he stepped onto the stage at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, Hartmann’s art had gone international.

These days, it seems that Hartmann’s most famous covers are the ones he didn’t design. A persistent rumour that he designed the cover for Steely Dan’s Aja isn’t all that far-fetched, given the proximity of Poco — bassist Schmidt sung backing vocals on three Aja tracks — and the minimalist bent that characterised some of Phil’s work. It’s nice to believe that Hartmann might’ve been hip to the Dan, but Aja owes its striking cover to photographer Hideki Fujii and graphic designers Patricia Mitsui and Geoff Westen. It’s also easy to see why some believe that Hartmann was responsible for America’s Hearts, but that cover was designed by the ever-prolific Gary Burden.

That being said, there are more Hartmann covers out there. The man himself ballparked his folio at “more than 40” pieces, but Discogs puts just 21 covers to his name, suggesting that there’s just as many still waiting to be exhumed, their attributions yet to make it to the internet. It could be that they’re long out of print, tethered to minor projects that have since faded from our collective memory, or perhaps it’s an issue with credits, like his Crosby, Stills and Nash logo.

That’s stuff we might never know. If one thing’s for sure, it’s that whether you know him as Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Lionel Hutz or Troy McClure, you might remember Phil Hartman from more places than you’d think.